When Julian Barnes, 2011 winner of the Man Booker Prize, was asked (2006) whether the readers of Arthur and George expected him to name the culprit in that novel, he replied, “Well, one or two were disappointed that they didn’t find out. That’s why it’s a novel, and not a detective story” (Conversations, 146). The same kind of answer could perhaps be given to  readers who were similarly disappointed by The Sense of an Ending, Booker prize-winner. You need only peruse the readers’ reviews on Amazon to sense some irritation because the novel does not really solve the mystery it sets up. The central character, a not very remarkable man in later middle age, is accused at key junctures of the novel of “not getting it,” and some readers in their comments pick up quite angrily on this, along the lines of “Who can blame him? I don’t get it either.” Barnes drops clues throughout the novel, but in the end readers don’t quite get it, any more than the central character does. Some people object to this, and many don’t. In any case, perhaps Barnes would again say, that’s why it’s a novel and not a detective story.

readers who were similarly disappointed by The Sense of an Ending, Booker prize-winner. You need only peruse the readers’ reviews on Amazon to sense some irritation because the novel does not really solve the mystery it sets up. The central character, a not very remarkable man in later middle age, is accused at key junctures of the novel of “not getting it,” and some readers in their comments pick up quite angrily on this, along the lines of “Who can blame him? I don’t get it either.” Barnes drops clues throughout the novel, but in the end readers don’t quite get it, any more than the central character does. Some people object to this, and many don’t. In any case, perhaps Barnes would again say, that’s why it’s a novel and not a detective story.

In a detective story, you can legitimately hope to get it by the end. The writer of a detective story cannot however legitimately hope to get the Man Booker Prize, the UK reward for the “very best book of the year.” Dan Kavanagh, writer of four crime novels, has never been short-listed for the Booker Prize, as Barnes was three times before winning it, even though Dan Kavanagh is Julian Barnes and Julian Barnes is Dan Kavanagh. “Life is not a detective story,” said Barnes in the same Conversation of 2006. “In life you don’t necessarily find out who did it” (146). In Dan Kavanagh’s novels, you do find out who did it. Is that why they are detective stories, and not novels—not novels at any rate that would be in the running for the Booker Prize?

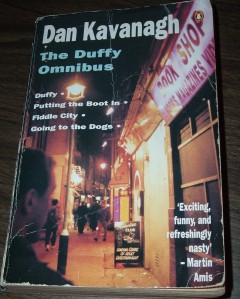

Intrigued by this whole question, I recently read all four novels in Kavanagh’s one-volume The Duffy Omnibus—not so easy to get hold of anymore, but there are some secondhand copies available, here and in the UK. I learned of the existence of Duffy through reading a piece by Declan Burke in his blog, the title of the piece a nice demonstration of crime-writer Burke’s wit and precision: “On Putting the Boot into the Booker Prize.” When he heard that Barnes had won the prize this year, he vaguely remembered liking two of Barnes’ earlier novels but didn’t remember too much about them; on the other hand he did remember hugely enjoying Kavanagh’s Putting the Boot In, the third of the Duffy novels set largely in a local professional Third Division football club in London. “So there you have it,” writes Burke, “ a Booker Prize winner with a rather decent half-canon of crime novels under his belt . . . Have we shuffled another step closer to the day when a fully-fledged crime writer scoops the establishment’s glittering prize?”

one-volume The Duffy Omnibus—not so easy to get hold of anymore, but there are some secondhand copies available, here and in the UK. I learned of the existence of Duffy through reading a piece by Declan Burke in his blog, the title of the piece a nice demonstration of crime-writer Burke’s wit and precision: “On Putting the Boot into the Booker Prize.” When he heard that Barnes had won the prize this year, he vaguely remembered liking two of Barnes’ earlier novels but didn’t remember too much about them; on the other hand he did remember hugely enjoying Kavanagh’s Putting the Boot In, the third of the Duffy novels set largely in a local professional Third Division football club in London. “So there you have it,” writes Burke, “ a Booker Prize winner with a rather decent half-canon of crime novels under his belt . . . Have we shuffled another step closer to the day when a fully-fledged crime writer scoops the establishment’s glittering prize?”

Somehow, I doubt it. In a recent article in the Guardian, the week in 2010 when the Australian crime writer, Peter Temple, won the top Australian literary prize, the Miles Franklin Award, Alison Flood discussed the possibilities of a detective novel’s winning the Booker prize. The former chairman of the Booker judges, John Sutherland, has said that he doesn’t expect it any time soon. Flood quotes him as saying: “The twice I’ve been on the Booker panel, they weren’t submitted. There’s a feeling that it’s like putting a donkey into the Grand National.” Oh dear. Strong words indeed. Sutherland fears that awarding a mainstream literary prize to a work of genre fiction would devalue the reputation of the prize. But best-selling crime novelist, Ian Rankin, thinks that attitudes are shifting: “Slowly the barricades are falling,” quotes Flood. She also quotes Morag Frazer, however, a Miles Franklin judge for past six years, who suggests that most crime novels will never win the Miles Franklin or any other literary prize “because they do not work the language hard enough, and they do not think originally and with sufficient depth and imagination . . . they may gratify, but they do not surprise the way great literature does.”

The question of gratification versus surprise brings us back to Barnes’s suggestion that a novel does not have to name the culprit as a detective story does. One of the ways the detective novel surely gratifies is in its ultimate naming of the culprit. Michiko Kachitani, reviewing Barnes’s The Sense of an Ending in the New York Times recently called it “a sort of psychological detective story,” and says that it manages to create genuine suspense. And so it does. The central character, Tony, is searching his own memory for an understanding of the past, and of how the past created his own present. Throughout the novel, one senses that an explanation of the key mystery is just around the corner. Why did his college girl-friend treat him as she did? Why did his old friend commit suicide? Why did his girlfriend’s mother leave him five hundred pounds and his old friend’s diary? Why did his girlfriend then withhold this diary from him – and from us, the readers –so that we never really know for sure why his friend did what he did? We are allowed to read only a tantalizing extract from the diary, as is Tony. Yes, a dramatic disclosure at the end of the novel opens Tony’s eyes, and ours, to a part of the story, but he will never know it all, and nor will we.

When Barnes said, life is not a detective story, in life you don’t necessarily find out who did it, he was talking, not about The Sense of an Ending but about Arthur and George, a novel based on a real crime story: in 1903, George Edalji was accused and convicted of the ugly crime of ripping horses open with a knife, wrongly accused and wrongly convicted, and ultimately vindicated by the efforts largely of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. This was a real case, and here Barnes certainly “manages to create genuine suspense.” This is a page-turner and one follows anxiously the ins and outs of the case. Edalji is finally vindicated in part, as he was in reality, but the actual culprit is not/was not found. Precisely because the novel is built up with much suspense centering on the figure of George, it is surely frustrating to the reader of the novel when the crime is never actually solved (I speak for myself), but of course Barnes could not invent a solution to a real crime that in reality was never solved. In life, you don’t necessarily find out who did it. In The Sense of an Ending, where we know that Barnes, the writer, has created the story, has created the mystery, it seems to be a more arbitrary thing, this withholding of a solution. Does it perhaps make the novel more of a novel, more of a candidate for literary prizes, to leave the mystery only half-solved? Well, yes, it probably does, but this is a cynical way of looking at it. The Sense of an Ending does capture in a tantalizing way the real inadequacy of memory in reconstructing one’s own past—and so it is closer to life than a detective story where all is made ultimately plain.

When Barnes said, life is not a detective story, in life you don’t necessarily find out who did it, he was talking, not about The Sense of an Ending but about Arthur and George, a novel based on a real crime story: in 1903, George Edalji was accused and convicted of the ugly crime of ripping horses open with a knife, wrongly accused and wrongly convicted, and ultimately vindicated by the efforts largely of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. This was a real case, and here Barnes certainly “manages to create genuine suspense.” This is a page-turner and one follows anxiously the ins and outs of the case. Edalji is finally vindicated in part, as he was in reality, but the actual culprit is not/was not found. Precisely because the novel is built up with much suspense centering on the figure of George, it is surely frustrating to the reader of the novel when the crime is never actually solved (I speak for myself), but of course Barnes could not invent a solution to a real crime that in reality was never solved. In life, you don’t necessarily find out who did it. In The Sense of an Ending, where we know that Barnes, the writer, has created the story, has created the mystery, it seems to be a more arbitrary thing, this withholding of a solution. Does it perhaps make the novel more of a novel, more of a candidate for literary prizes, to leave the mystery only half-solved? Well, yes, it probably does, but this is a cynical way of looking at it. The Sense of an Ending does capture in a tantalizing way the real inadequacy of memory in reconstructing one’s own past—and so it is closer to life than a detective story where all is made ultimately plain.

But what about our man Duffy, the tough, bi-sexual ex-cop, now owner of the one-man business, Duffy Security, who brings all four of his mysteries to a gratifying solution, the first one, Duffy, set in the sleazy territory of pimps, prostitutes, punters and porno in London’s Soho, the second one, Fiddle City, in an airport setting that will put you off flying from Heathrow ever again, the third one, Putting in the Boot, in a football club, and the fourth one, Going to the Dogs, in an English country-house the likes of which you will never have seen in a cozy murder mystery. What are these mysteries? No, not Booker Prize winners. Yes, detective stories. Not novels then? Not life? Not Julian Barnes? In his printed books, they are generally not included in the lists, front or back, of his earlier works. In the British Council Newsletter, Literature Matters, we are told that Julian Barnes is, among other things, a “master of suspense in the persona of his alter-ego, pulp-fiction writer, Dan Kavanagh.” Julian Barnes, one might suggest, is a master of suspense in his Booker persona also. Are his Kavanagh novels “pulp fiction?” I think this whole question deserves a closer look. Please, readers, send in any comments or questions you may have.

the first one, Duffy, set in the sleazy territory of pimps, prostitutes, punters and porno in London’s Soho, the second one, Fiddle City, in an airport setting that will put you off flying from Heathrow ever again, the third one, Putting in the Boot, in a football club, and the fourth one, Going to the Dogs, in an English country-house the likes of which you will never have seen in a cozy murder mystery. What are these mysteries? No, not Booker Prize winners. Yes, detective stories. Not novels then? Not life? Not Julian Barnes? In his printed books, they are generally not included in the lists, front or back, of his earlier works. In the British Council Newsletter, Literature Matters, we are told that Julian Barnes is, among other things, a “master of suspense in the persona of his alter-ego, pulp-fiction writer, Dan Kavanagh.” Julian Barnes, one might suggest, is a master of suspense in his Booker persona also. Are his Kavanagh novels “pulp fiction?” I think this whole question deserves a closer look. Please, readers, send in any comments or questions you may have.

I am also going to look in this context at another writer, known well in the literary canon who also wrote “detective stories” but who did not separate them off and write them under a different name: The Swiss writer, Friedrich Duerrenmatt. His name came up in my recent discussions, published in this blog, with Sally Spedding, chiller-thriller writer who is a great admirer of Duerrenmatt. Thinking then of what detective fiction was all about, I asked her what she thought of P.D James’ much quoted dictum that detective fiction was not about murder but about the restoration of order. Sally replied succinctly with a question: “What order?” Now be it said that P.D.James has been chair of the Man Booker Panel (1987) but she has never had a novel nominated for the Booker Prize. She is certainly the grande dame of UK detective novels. She certainly brings all her novels to a gratifying conclusion in the sense of leaving us with a clear sense of who did it. She does, in her own work, restore her own order. Barnes’s Booker-eligible novels are not about the restoration of order. When he says, “In life you don’t necessarily find out who did it,” he also says, “you don’t necessarily get justice” (Conversations, 146). You do find out who did it in his provocative, often shocking, often very funny detective novels, but do you get justice? What order (see Spedding) is there to restore in the world of Duffy? Starting point for another piece.

As D. Michael Risinger has argued in ‘Boxes within Boxes’, ‘Arthur and George’ is a kind of morality tale in which it is assumed from the start that George is innocent. I think the real George very probably was innocent, but the historical evidence is not quite as clear-cut as the novel suggests. Researchers such as Michael Harley have claimed that the man who believed in fairies may have been taken in by the seemingly inoffensive young solicitor from Staffordshire. If it is not absolutely certain that George was innocent, certainly of writing the anomymous letters which helped to convict him, then it is not logical to ask that we should be told the name of the real culprit. Conan Doyle’s suspects might be named, and the evidence against them might be produced, but that is far as anyone can now go.

Incidentally, your description of the charge against George is not quite accurate. He was accused of wounding a pony, just the eighth of the series of animal outrages in Great Wyrley in 1903. No one was ever accused of committing the earlier crimes. It is a matter of speculation as to what kind of weapon was used in the attack on the pit-pony. It might not have been a knife. Indeed, Conan Doyle suggested that his suspect could have used a horse-lancet..

For anyone interested in weighing up the evidence my book ‘Outrage: The Edalji Five and the Shadow of Sherlock Holmes’ (Vanguard Press) offers a comprehensive survey. It also contains an analysis of the extent to which the account in ‘Arthur and George’ remains true to the actual historical record.

Thank you for this very useful comment. I’m afraid I wrote the piece simply taking on faith the Barnes version of the “Arthur and George” story. I shall be most interested in reading your analysis of the whole case in your book “Outrage.” Thank you too for your correction of my description of the charge against George. It is indeed a fascinating business!

Fascinating, Dorothy! I had no idea of the Barnes/Kavanagh connection. Reminds me of John Banville/Benjamin Black and I would love to be a fly on the wall if the two men ever sat down and chatted about their dual roles. (For all I know, they have?)

As for a book ending without a concrete solution, I never mind that as long as the journey to that point was worth my time. In the case of this year’s Booker, I felt cheated all around.

Thanks, Ellison! I must admit, I have not read Banville/Black — but I think I should! Hope to do the piece on Kavanagh pretty soon.

I think it is interesting that a lot of people informally admit feeling cheated by the”Sense of an Ending” but formally –i.e. in the case of many published reviewers to say nothing of the Booker Panel — the general tone is of adulation. We’ll see how it wears in the long run.

Excellent, Dorothy. In-depth and really interesting. Also topical. Am now looking forward to reading your exploration of the memorable Friedrich Durrenmatt.

Pingback: Julian Barnes's "The Sense of an Ending"

Very interesting post. I’ve read only the first Duffy novel, along with Arthur and George and The Sense of an Ending, so I don’t have a comprehensive view of Barnes’s writing. I’ve read in a number of places that Barnes probably won the Booker as a sort of lifetime-achievement award and not for The Sense of an Ending in particular.

I’m a person who loves and is frustrated by books that get a lot of critical or prize-finalist love, so I look forward to your future posts.

Thanks, Rebecca, I’ve been mulling over the questions I raised in this post, questions of why some novels are candidates for literary prizes and some (e.g. detective novels) are generally not, as well as questions of what order detective novels can possibly restore (see P.D.James), and I am trying to find some answers, Sally, by looking at your admired “The Pledge” of Duerrenmatt. Want to publish this post soon. Thank you both for your encouragement

An extremely interesting post. I enjoyed the first Duffy book most, and The Sense of an Ending is terrific. Like Sally, I’m a Durrenmatt fan.

Thank you for this comment, Martin. I’m glad you read the post. Not too many people are interested in the Duffy novels. I agree that the first one is probably the best. I have now read and enjoyed your piece on “The Sense of an Ending.” I keep meaning to go back and write some more about Duffy, but haven’t got to it yet.